33. Achieving Sight-Singing Success…

… is so easy,

and it starts with the simple means of teaching of Sight-Singing

as demonstrated in my two articles on this Blog numbers 15 & 16

Dr John Bertalot

Organist Emeritus, St. Matthew's Church, Northampton

Cathedral Organist Emeritus, Blackburn Cathedral

Director of Music Emeritus, Trinity Episcopal Church, Princeton, NJ

Former Adjunct Associate Professor, Rider University, Princeton NJ

Former Senior Lecturer, Royal Northern College of Music, Manchester

(That’s enough to be going on with!)

Assuming that you have taught your young choristers to sight-sing in the way I suggest

(see my articles 15 & 16 on this blog)

which demonstrate that the secret is to get them to tell you what it is that you want to tell them,

and then take ENORMOUS genuine delight when they give the right answer:

then the only reason

why your choristers still can’t sight-sing to the high standard that you had hoped for them

is entirely due to the way in which you lead your rehearsals!

Let me say that again:

*The only reason

why your choristers still can’t sight-sing to the high standard that you had hoped for them

is entirely due to the way in which you lead your rehearsals!

**…It’s entirely due

to the way in which you lead your rehearsals!

1. DIFFICULT?

The difficult part is how to enable one’s choristers to make use of, and daily to improve, their newly-learned sight-singing skills.

WARNING: Don't be like this! When I led a choral workshop for over 100 choirmasters and 200 children in Chicago a few years ago, I demonstrated to the choirmasters how I taught children to sight-sing.

One of the choirmasters said, ‘I spend the first five minutes of every rehearsal doing just that.’ But then she went on to say, ‘Of course, for the rest of the practice the children have to learn the notes by rote, for there isn’t time for them to sight-sing new music.’

I confess that when she said that I nearly threw up, for she negated all her teaching by saying, in effect, it’s all very well knowing the theory, but it doesn’t work in practice!

And so, dare I say it, that is precisely what so many choirmasters do – they may teach their children about note values, and sharps and rests and expression marks, but when it comes to leading a rehearsal they play all the notes for their children, and automatically tell them that they should have sung this note instead of that note, and that they should sing that phrase softly instead of loudly, and ‘this is how it goes’.

Once choirmasters do that – and so many of us do – that immediately destroys any initiative in sight-singing skills that a chorister may have wished to use.

2. THE ESSENCE OF SIGHT-SINGING

You know that the essence of singing at sight is to hear for oneself what the next note should sound like. It’s different from sight-reading on a piano for which one only needs to know which key to press, regardless of its pitch.

It’s like reading a book about weight-loss. ‘Yes, I agree with everything that’s written, and I know that diet and exercise are essential.’ And then the reader continues to sit in a chair and wonders why he’s not losing weight! Skills have continually to be put into practice to make them work.

Are you enabling your choristers to put into practice DURING REHEARSALS the sight-singing skills you have taught them?

So this is how your choristers can put the theory you've taught them into practice:

3. NEVER PLAY ‘THE TUNE’

When one does play the piano for trebles’ rehearsals,

by all means play the harmony – but not the tune.

One new cathedral Director of Music told me recently that when he took the first practice with his choristers and played just the basic harmony with the bass line, but not the tune, his choristers didn’t know what to do, for they had been so used to following the tune which his distinguished predecessor had always played.

But after his choristers realised that they were now being challenged to think for themselves, their concentration and commitment began to increase by leaps and bounds.

It was my privilege (and somewhat surprised delight)

to demonstrate to the Annual Conference of 30 Directors of Music of UK Cathedrals at Exeter Cathedral in 2013 just how easy it is to teach children to sight-sing (using the methods in my articles 15 & 16).

just how easy it is to teach children to sight-sing (using the methods in my articles 15 & 16).

Four Exeter probationers worked with me for 45 minutes

(they clearly enjoyed the experience - look at their smiles!)

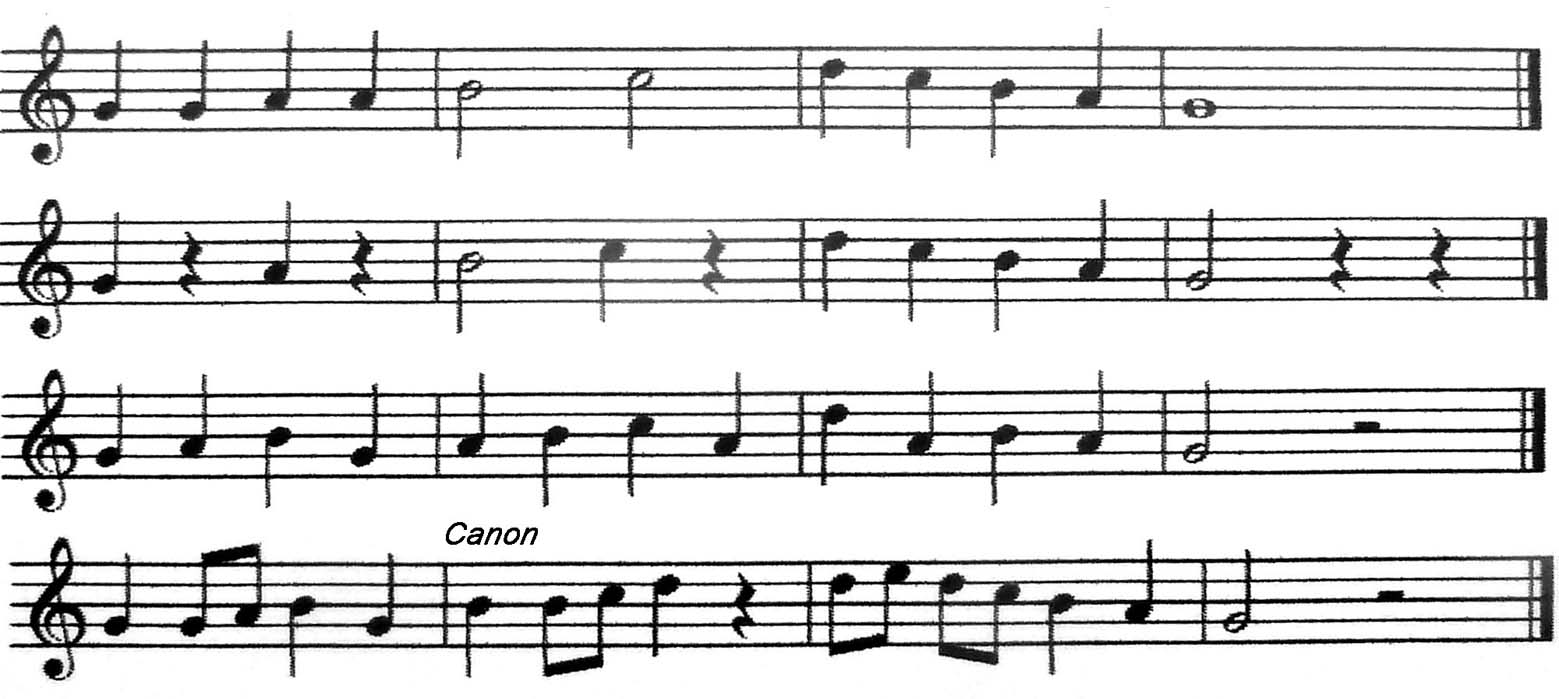

after which they could sing a four-bar melody absolutely correctly -

and what's more, they could sing it in as a two-part canon!

These were the melodies they sang - working very slowly from clapping crotchets, and minims and semibreves,

then working very steadily on pitch (does it go up or down? 'It stays the same!')

Then clapping rests.

But going so slowly that the children got everything right the first time,

and so they continually felt encouraged and grew in confidence.

(The best teachers teach hope, not despair!)

But if one is going to lead children's singing from the piano , as so many do,

you'll find that they can sing the tunes -

because they copy what you have just played,

a fraction of a second after you've played it!

To demonstrate this, I asked the Cathedral Directors of Music to sing Mary had a little lamb to a tune that I had composed (at vast expense), but I didn’t give them the music – just the words.

I played the introduction and then I led them from the piano. And, my goodness, they made a pretty creditable attempt at singing it. How? Because I was playing the tune as well as the harmony, so they sang the notes that I played a fraction of a second after I’d played them, and sometimes they could even guess what was coming next.

This is a skill which all children have, and their choirmasters think that they are sight-singing.

They're not, they're copying what you're playing!

And so, if you want your children to become skilled sight-singers, NEVER PLAY THE TUNE!

4. I DARE YOU TO TRY THESE EASY IDEAS

TO STIMULATE YOUR CHORISTERS,

FOR THE REALLY DO WORK!

At the start of every trebles’ rehearsal

ask the children to pitch an ‘A’ without having it played on the piano.

(‘A’ is a good note to be able to pitch, for it’s the note that orchestras tune to, and it’s a note that children can sing with their head tone. i.e. don’t ask them to sing middle C.)

Why ask them to pitch an ‘A’ out of the blue?

Because it immediately challenges the children to look at the music creatively and to think.

Enabling one’s young singers to think is the whole secret of constructive choir-training. They have to think in order to be able to sight-sing.

And so, when the children arrive for their rehearsal they know full well that they will be challenged to think (not to copy) – and children love challenges which they can meet.

Does it matter if they don’t pitch the note wholly correctly at first?

No – what matters is that they are given an opportunity to try.

But after a few rehearsals you’ll find that most of the children will be able to pitch an ‘A’ successfully, and this will excite them. (You do want a choir of singers who are excited to be with you, don’t you?)

But what a waste of time, some of you may think. No – when you use your limited time in rehearsals to encourage your singers to think, you are making the very best use of your time

But you may think that that’s OK for cathedral choirs, but not mine.

No – I did this in my retirement for 11 years with my village church choir in Lancashire – which was an adult choir made up mainly of grandparents, apart from those who were great-grandparents, as I've mentioned before.

They loved the challenge of trying to pitch the first note of a hymn they were about to rehearse.

They weren’t always right, for some were well advanced in years, but, my word, that repeated challenge made them sit up straight, both physically and mentally, and they smiled!

They loved those challenges – and so will your choir.

I did all this for 16 years with all my children at Trinity Church in Princeton, NJ, and they loved it.

Of course one has to start in easy stages – one thing at a time – but that’s how progress is made in any discipline.

To have a choir of thinking choristers (both children and adults) is the greatest possible joy, for it makes the choirmaster’s job so much easier and so much more rewarding.

It was my privilege, from time to time at Princeton, to welcome individual choirmasters who came to watch our practices. They had read my books on choir-training and wondered if what I had written worked out in practice. (It did!)

Choirmasters came from as far away as Canada, and from many parts of the USA including Seattle, Florida, Los Angeles and San Francisco.

One choirmaster flew all the way from New Zealand to watch my practices!

I was astounded – but he said that his journey was worthwhile when he saw what the children were achieving!

One musician from Texas told me that she hadn’t realised that when one has a choir of skilled sight-singers there was generally no need for note-learning. ‘You started polishing new music straight away,’ she told me. Think how much time that saved!

NOW, TRY THIS!

Ask the children to pitch the first note of every piece of music which they are about to rehearse

before you start rehearsing it.

That means that they will have to look at the notes creatively.

(My village church choir of senior adults did this with increasing success.)

Therein lies the whole secret of encouraging the skill of sight-singing: looking at notes creatively. After a short time some bright child will try to sing the first note before anyone else without you asking! That will raise enthusiasm even more – to see who can sing the right note first!

Again, does it matter if they don’t pitch that first note wholly correctly?

No. What matters is that they try to pitch the note. It’s the effort, not the achievement.

But they will, in time, gradually increase their skills and so, after a few weeks, they will be able to pitch notes with increasing accuracy – and that will give them a thrill for they will realize that, under your leadership, they are achieving things they never dreamt of.

And once they realize that, you’ll never lose a chorister from your choir,

for they will know that being with you is

a wholly constructive

and educational

and building-up

and fun experience.

I know – I’ve been there: done that!

ANOTHER IDEA TO TRY

When you’re rehearsing the music – be it a hymn or an anthem – and something needs improving (as it does in every rehearsal) should you tell them what the problem was?

No! By this time you’ll realize that I recommend that you should always ask them so that they may take ownership of the right answer and thus take pride in getting it right on Sunday.

Thus their creative thinking will be encouraged – and so their singing, and their sight-singing and their commitment to you and their choir will steadily increase.

AND ANOTHER IDEA TO TRY

Ask for a volunteer to ‘have a go’ at singing that faulty passage correctly.

[Don’t think, ‘I haven’t got time for that!’]

Once you begin to use your limited time to encourage young singers to think for themselves

and to risk ‘having a go’ in front of their peers,

the enthusiasm of your singers will increase by leaps and bounds,

and so will their accuracy

Your volunteer should be allowed a second attempt if the first wasn’t successful. Ask, ‘What wasn’t quite right?’ and then let him (or her) try again. If it still isn’t right give him (or her) a metaphorical ‘Well tried’, and then ask someone else.

I cannot stress too strongly the practical wonderfulness of allowing individuals to ‘have a go’ in the midst of a trebles’ busy practice – for thus the enthusiasm and achievements of the whole choir will increase beyond your imagining.

But if you still say, ‘I don’t have time to do this’,

then you’ll be in the same position as that choirmaster in Chicago

for, by playing the piano all the time ...

(some illustrious choirmasters even play the first line of a hymn whilst their singers are finding their places,

and they even play hymn tunes when the choir is singing –

that also makes me want to throw up!)

...you are turning off the singers’ wish and ability to think for themselves –

and you’ll be training a lot of parrots.

And parrots, as we know from Monty Python, can so easily become ‘late parrots’! i.e. singers who are not wholly committed to your choir.

After my sight-singing demonstration at Exeter Cathedral, one of the cathedral Directors of Music told me,

‘I think I play the piano too much!’

Too right - he got the message!

Do you want a choir of beautifully trained parrots, or a choir of enthusiastically creative musicians?

Dr John Scott was a chorister at Wakefield Cathedral and Sir David Willcocks was a chorister at Westminster Abbey. Many choirmasters started their musical lives as young choristers.

Do you have any budding Scotts or Wilcockses in your choir right now? If so, what are you doing during rehearsals to encourage the embryonic Willcockes and Scotts to demonstrate their growing leadership during rehearsals?

It’s the easiest thing in the world to teach children to begin to sight-sing

and, by the same patient methods,

to enable them to increase their skills week by week,

but the most difficult thing in the world is

for choirmasters to change the way we lead our rehearsals.

We all lead our choir practices in our own set ways – and so it would take a terrific jolt to challenge us to risk trying something new, for we are all creatures of habit.

May this article have provided that necessary jolt!

Have you been jolted? If, so, what are you going to do about it at your next rehearsal?

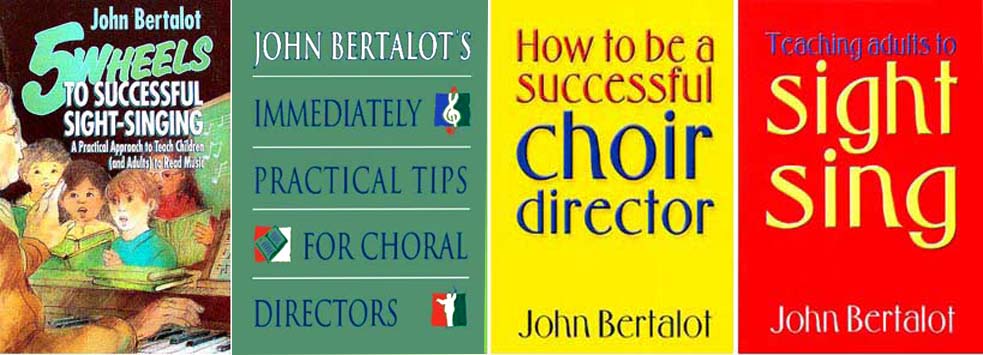

John Bertalot's best-selling first two books are available from Amazon,

and his third and fourth books are available from Kevin Mayhew,

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.